EXPERIMENTAL AESTHETICS

Exhibition in the Museum of Applied Arts in Vienna

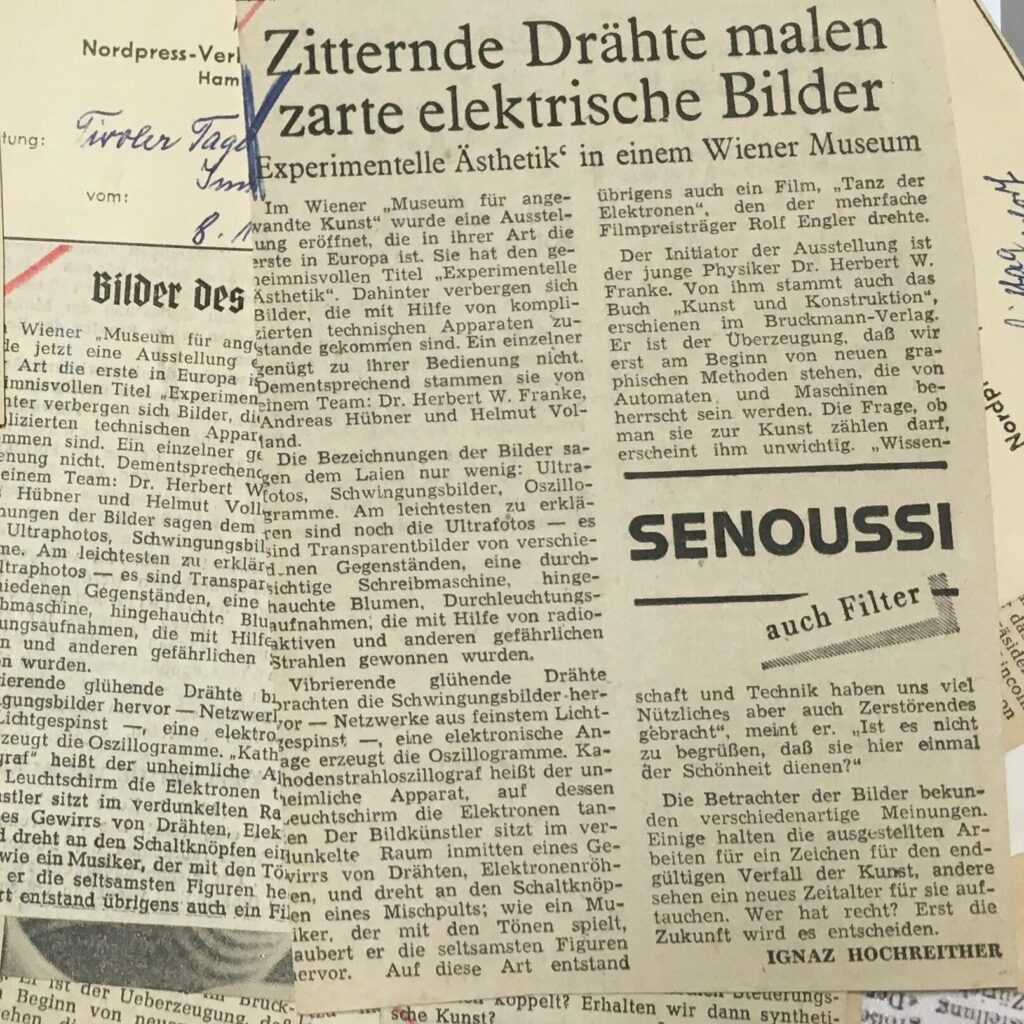

On January 3, 1959, an exhibition entitled Experimental Aestheticswith pictures by Herbert W. Franke opened at the Museum of Applied Arts in Vienna, whose art historical significance has only become clear in recent years: as the first exhibition in Europe in which electronic Images generated using electronic computing systems were shown. The title was intended to indicate that in these years art and art studies also gained interest from other perspectives than what wasthe casepreviously. This was demonstrated, among other things, by artists turning to new materials, moving objects and visually effective effects and optical illusions. So the path almost inevitably led to electronics.

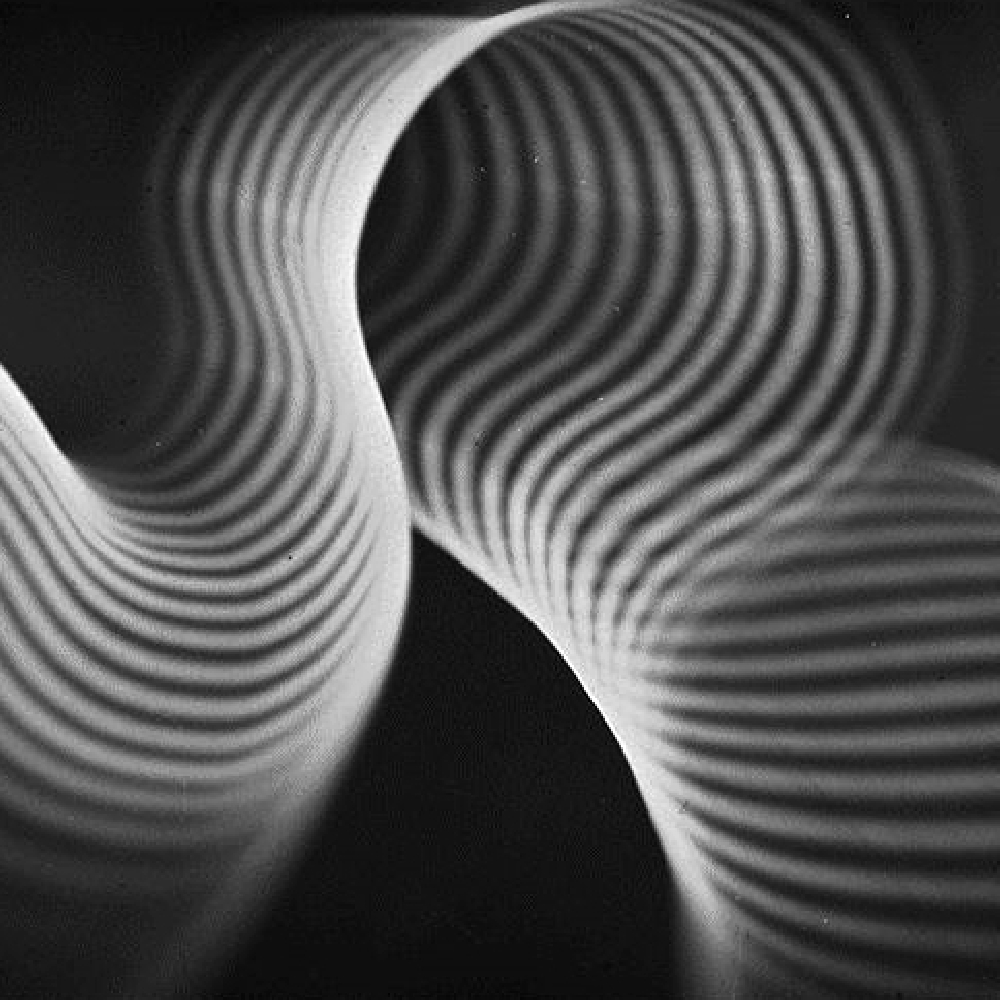

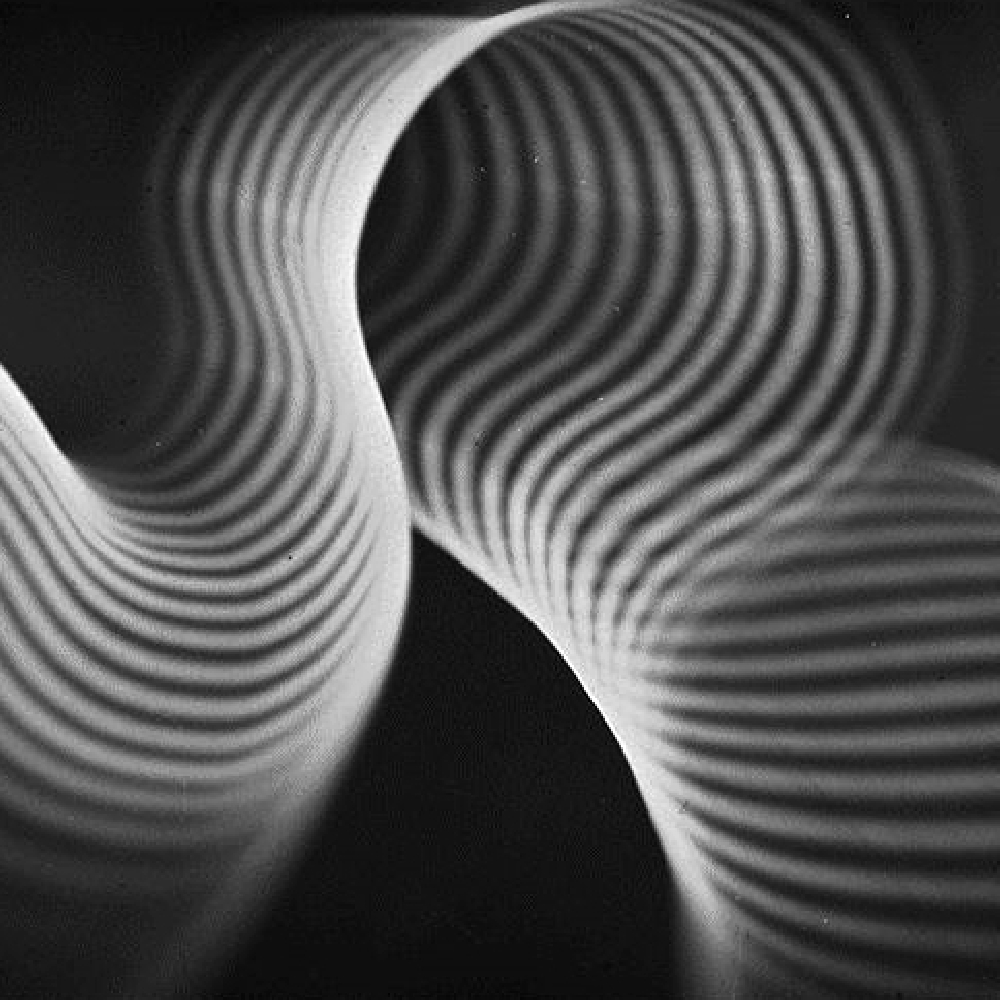

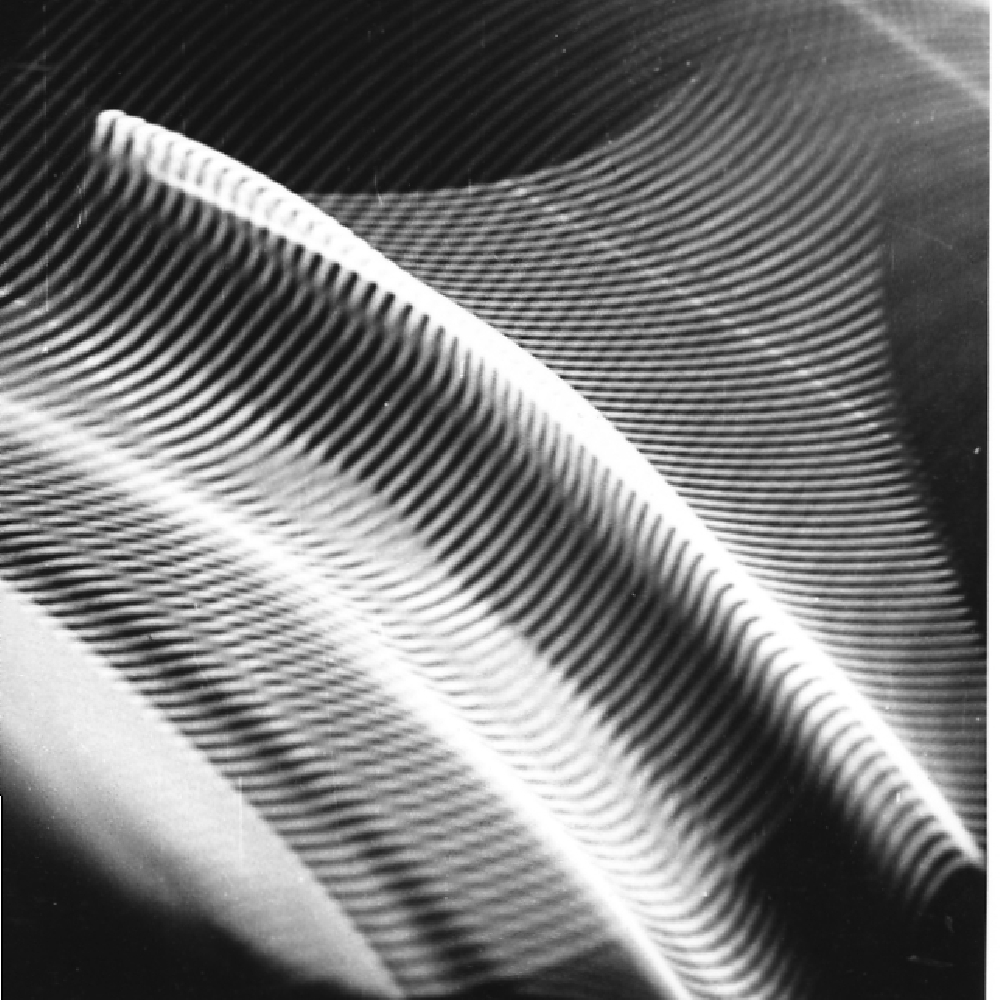

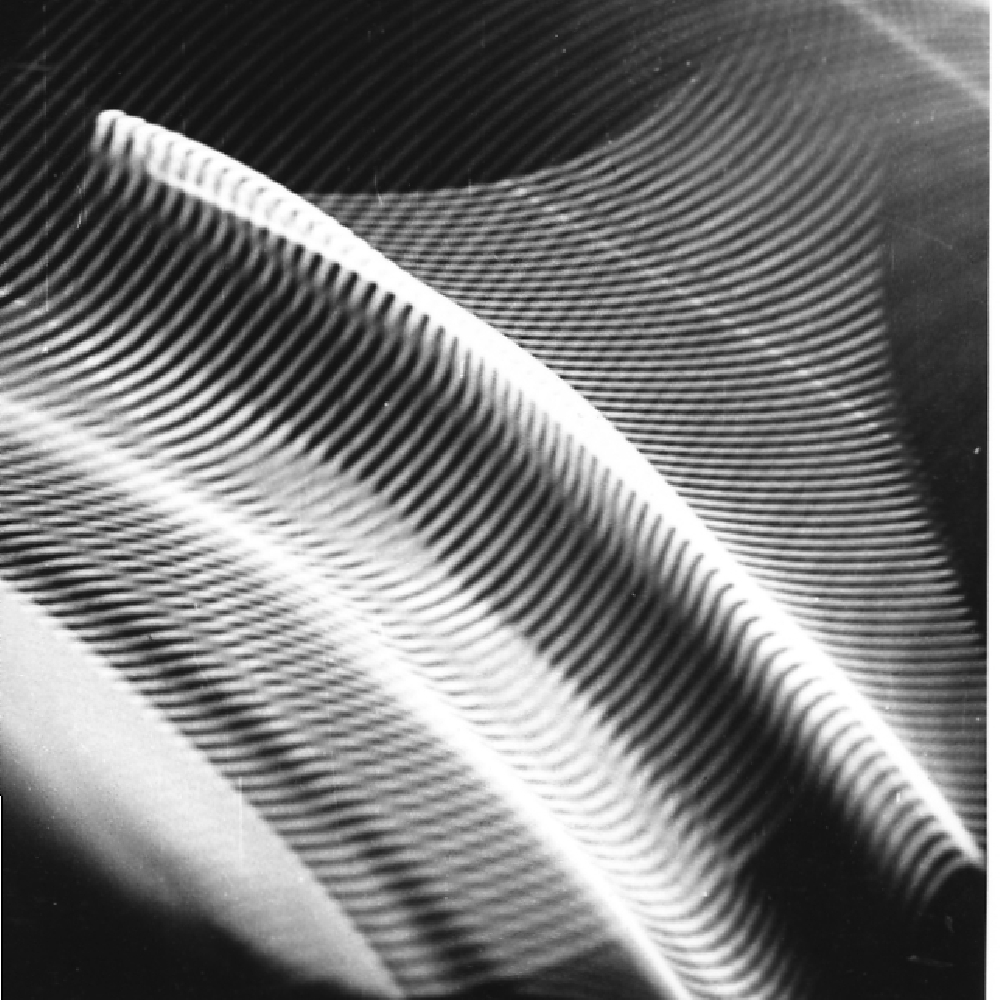

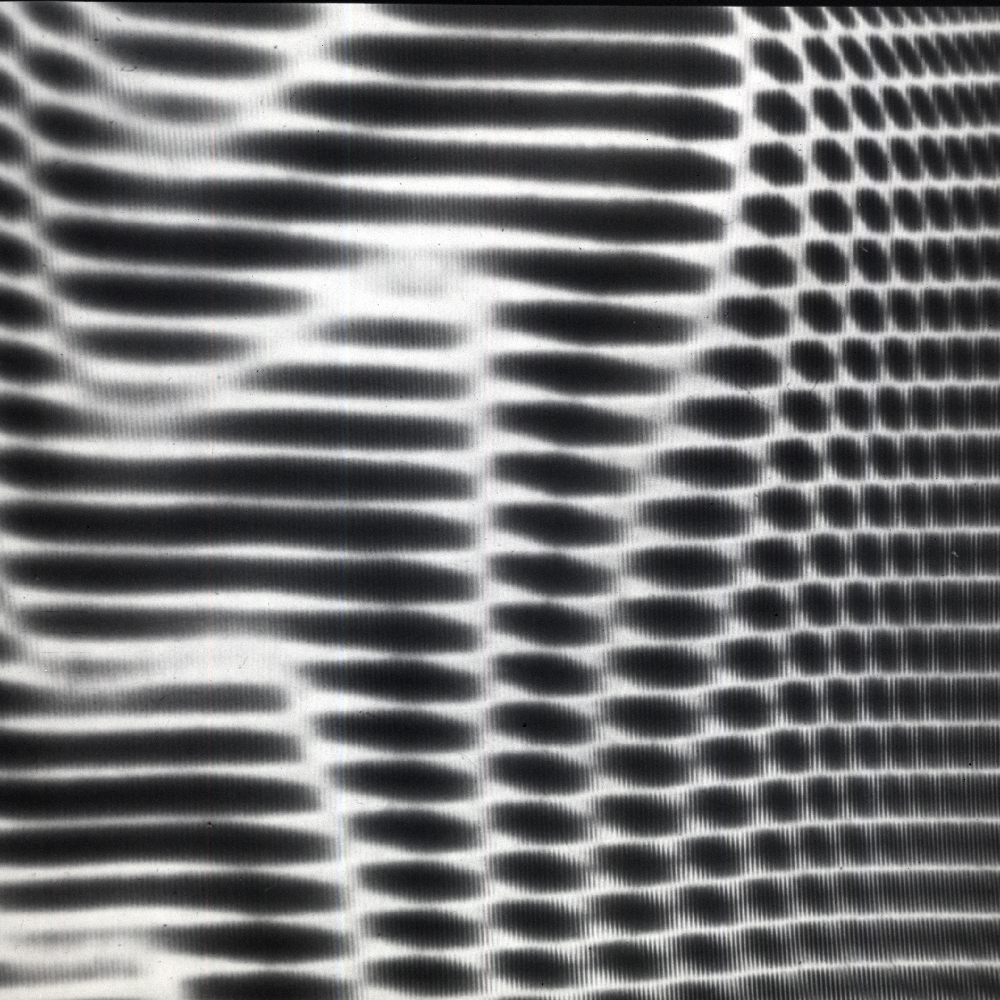

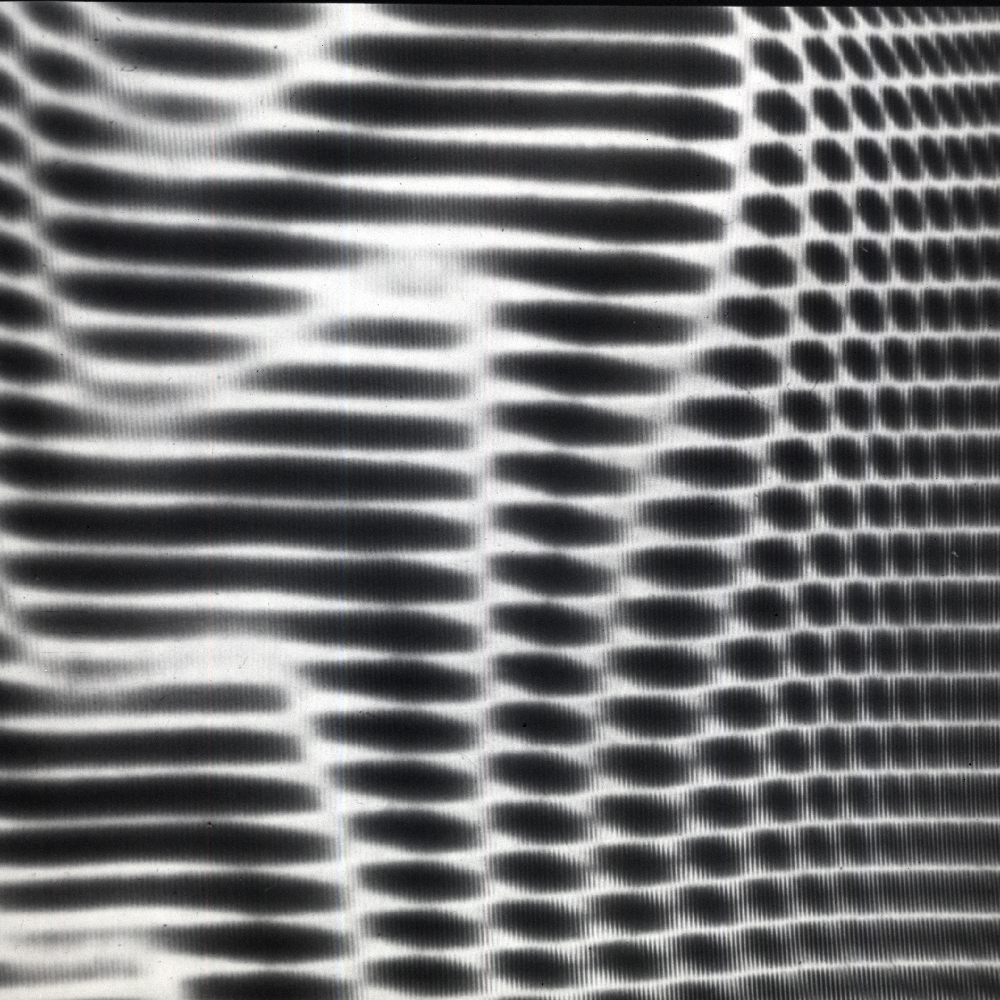

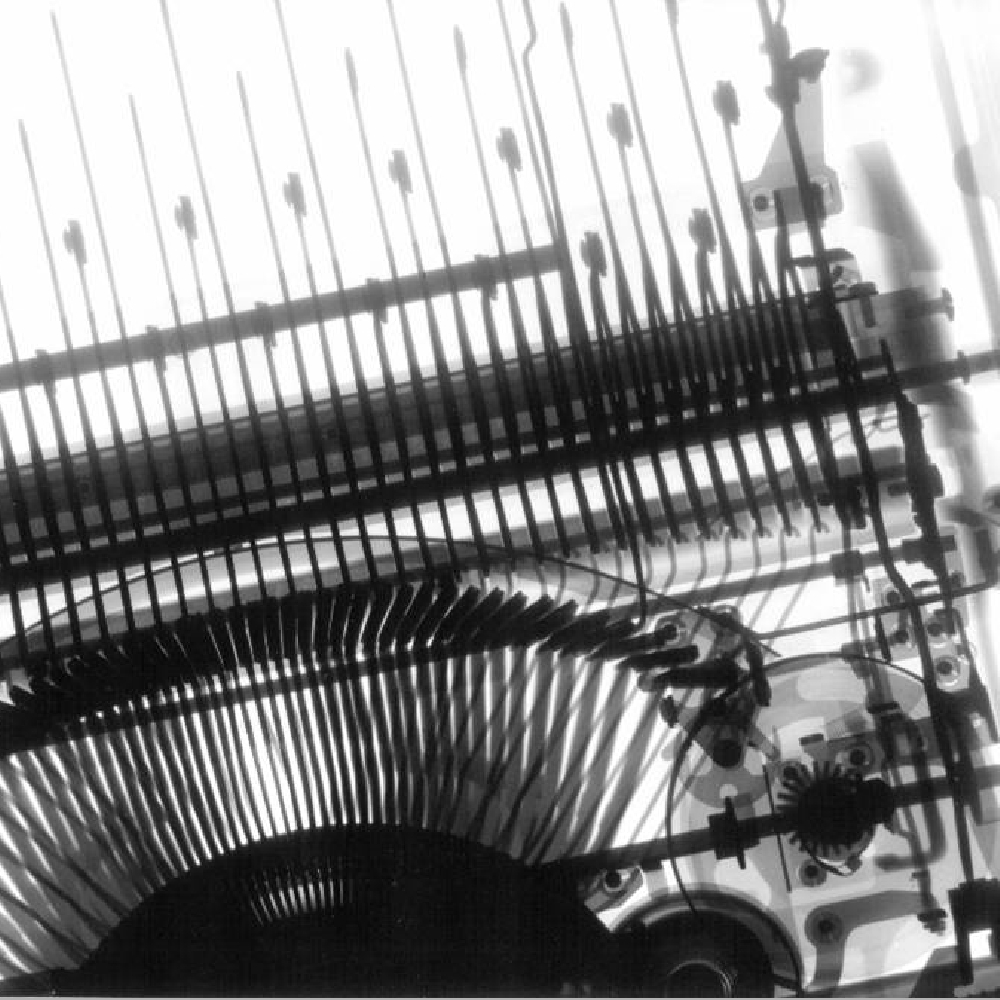

The first photo series ever was dedicated to experiments with vibrations; The images were created in collaboration with the photographer Andreas Hu bner and belong to the group Lichtformen(Forms of Light). This was followed by experiments based on elasticity and optical interference, and later also on high-energy electromagnetic radiation in the extended range of X-rays. Here, too, there was occasional collaboration with specialists, first with the physicist Paul Fries and later with the X-ray technician Helmut Volland.

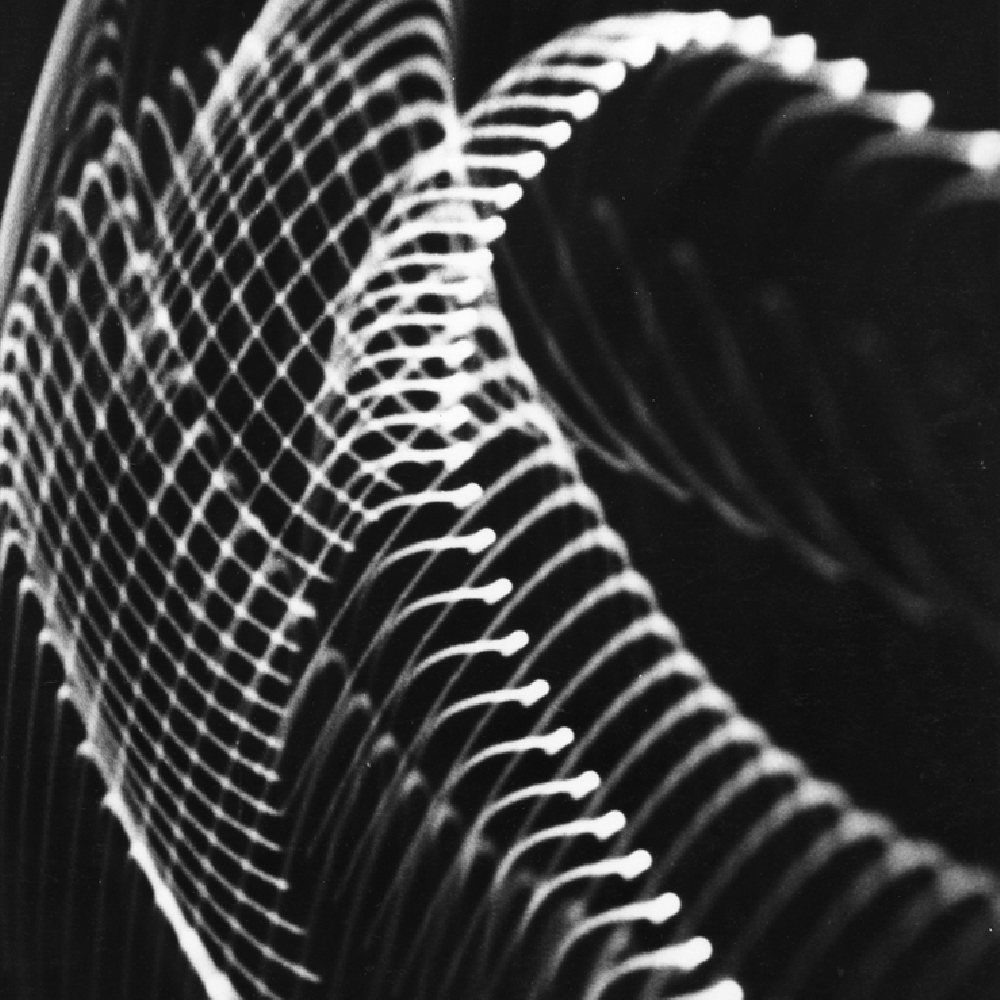

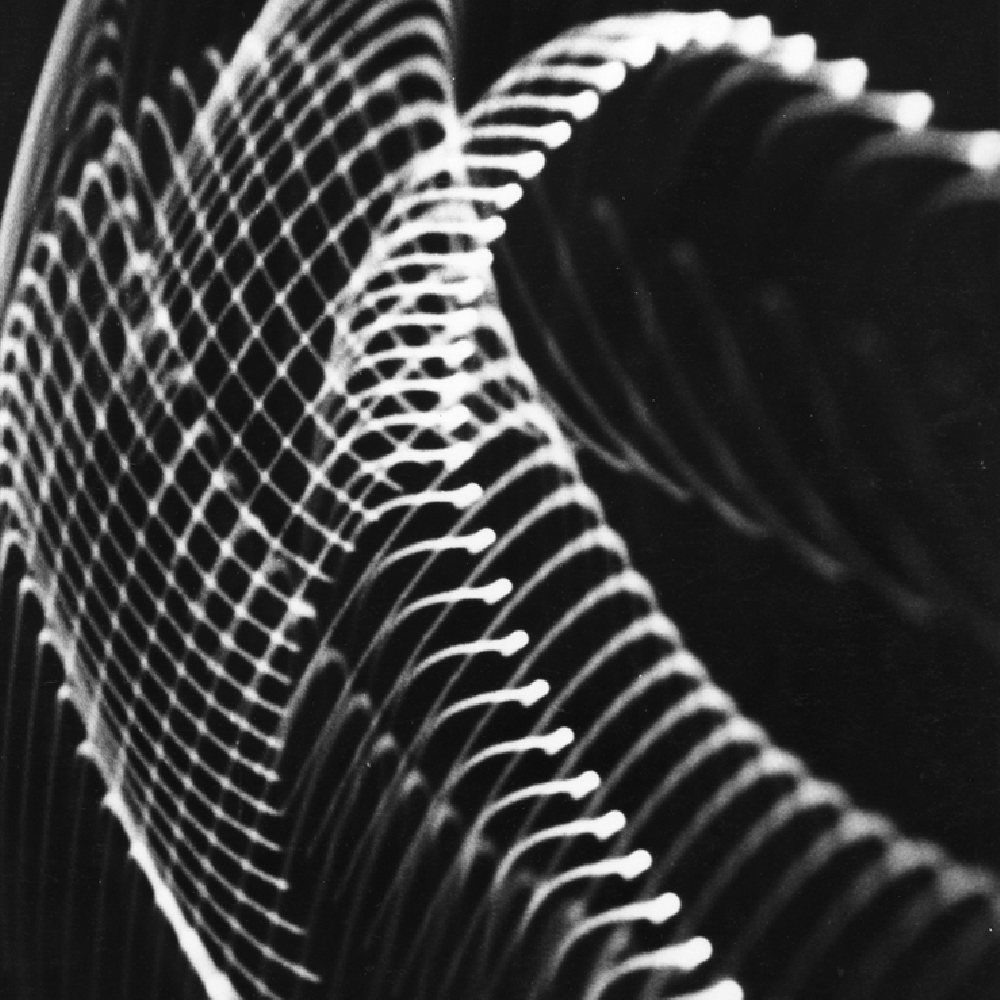

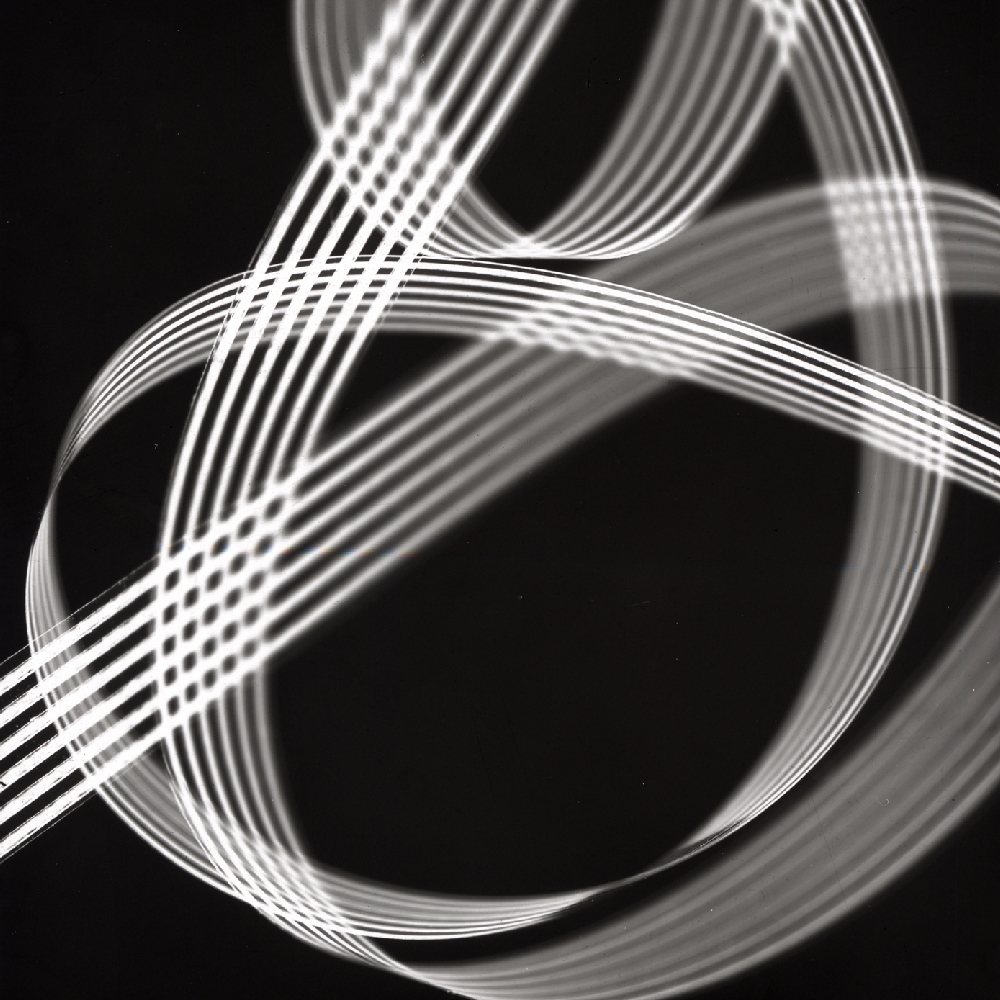

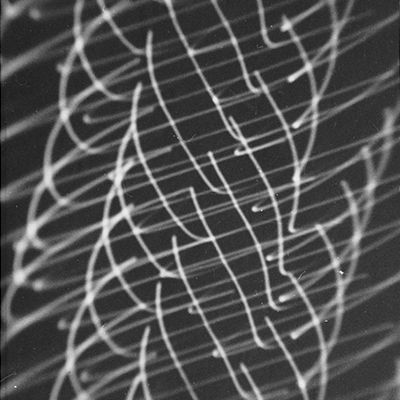

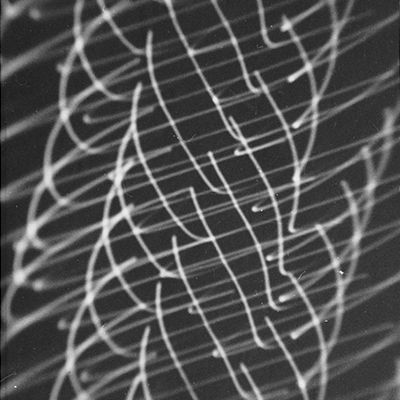

Since the middle of the 20th century, electronic laboratories have been equipped with a device called the cathode ray oscillograph, which can be used to visualize the voltage curve of electrical oscillations. Every now and then, graphically attractive shapes emerge, and some users have used them to create images that they offer for design purposes. The same device served Herbert W. Franke as the output device of an analog computer, the basis of the first algorithmically generated experiments. The computing system was developed and built by the Viennese physicist Franz Raimann in close collaboration with Franke. From a control board you could enter the parameters for those curves that served as graphic elements. The circuit was designed for interactive operation, the images could be calculated and controlled in their movement as under visual control on the screen.

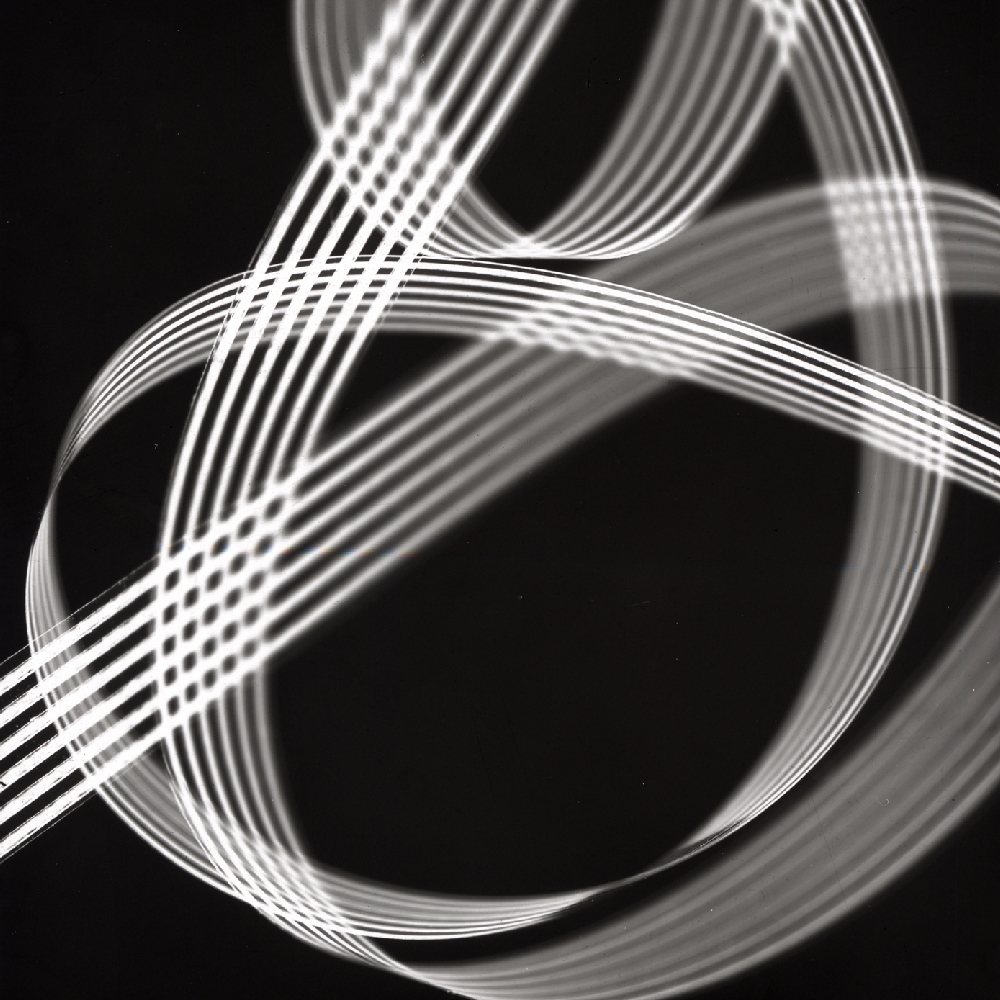

The circumstances surrounding this step into new creative territory were not ideal. The output device was a small oscillograph from an electronics hobbyist, on whose black and white screen the images were created. Since the diameter of the circular image surface was only five centimeters and the electron beam that produced the image could not be focused sharply, Franke often moved the camera past the screen when taking pictures, which resulted in evenly fanned out lines and gave the configurations a characteristic structure. The name of this series “Oscillograms”, which was created in December 1955, was derived from the output device used.

Later, around 1959, Franke had the opportunity to use his analog computer for visual experiments for a film project. This time, he had a high quality output device with a large screen at his disposal, with which he could also achieve gray tone gradients by drawing lines closely together. As a result, the image results took on a different style – to distinguish them, they were referred to as “electronic graphics” at the beginnin,g then as “Dance of the Electrons”. Incidentally, the film, which was supposed also to be called “Dance of the Electrons,” never made it to the public because producer Rolf Engler refused to comply with the television company’s request to replace the accompanying electronically generated music.

Although the electronically generated images in the exhibition received the most attention, the “Experimental Aesthetics” image show also contained other notable exhibits whose common characteristic was the origin of their concepts from science and technology. It is also worth mentioning that the person of Herbert W. Franke also reflects a historical component: namely the turn to electronic media that also applied to art in this time. This burgeoning interest came as a surprise to some art historians and critics, but signs of it could have been found in the music scene, where the transition was already well underway by the end of the 1950s.

The Vienna exhibition can also be seen as an illustration of this art transition to electronic media. That lies in the person of the physicist Herbert W. Franke. He wrote his dissertation on a chapter in electron optics and was therefore exposed to problems relating to the message and quality of images in a way that was far removed from art. But this is how he became aware of the striking aesthetic quality of the results of scientific photography in many examples. This gave him the idea that their devices could also be used in very atypical ways: namely, as instruments for creating aesthetic structures. Franke mused back in the 1950s that one could even develop devices that deliver images that are less concerned with scientifically relevant statements than with aesthetic effects. Such considerations were followed by a whole series of questions concerning art itself, but also its connections with science and technology.

This is also the reason why Franke turned to rational art theory. Only there could one hope for knowledge that would say something concrete about the questions he raised. Andhe also accompanied his considerations in the sense of a scientific way of thinking with experiments -which is also expressed in the term he coined: experimental aesthetics.