Herbert W. Franke

A Life between Art and Science

Herbert W. Franke, born in Vienna on May 14, 1927, studied physics and philosophy at the University of Vienna, and received his doctorate in 1951. In 1980, the Austrian Ministry of Education and the Arts awarded him the professional title of professor, and in 2007, he received the Austrian Cross of Honor for Science and the Arts First Class. In addition, the University of Design Karlsruhe granted the pioneer an honorary doctorate for his work in the field of art and science in 2018.

Overview important publications of Herbert W. Franke (in German)

The life of Herbert W. Franke can be defined by three main fields of work, which will be briefly outlined in the following, enabling an insight into the diversity of his work. His intellectual work is equally based on the rationality of a researcher and the creativity of an artist, two qualities ideally combined in him. His entire life was characterized by the bridging of these “two cultures” – at the center of which was the search for new territory. In 2010, Franke summarized this in the book Leuchtende Bilder with the following words: “Voyages of discovery, explorations of unknown terrain, have always meant much more than the acquisition of knowledge. They are an experience of character forming significance, one aspect of which being the confrontation with a new world of forms never seen before.”

which was dedicated to the artist and scientist Herbert W. Franke at ZKM | Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe in 2010

Herbert W. Franke and the Visual Arts

While still being a student, Franke began to show an interest in imaging systems. His dissertation on a topic dealing with electron optics initiated the impetus to engage with the question of how scientific images by technical apparatus are linked to art and aesthetics. As an amateur musician and photographer at the time, he was fascinated by the creative possibilities offered by the use of such machines for the production of aesthetic pictorial works. He began his first artistic experiments in the fifties, using cameras and a variety of machines such as X-ray apparatus to generatively produce works of art.

As a pioneer of machine-generated art, Herbert W. Franke created graphic artworks with highly diverse methods and devices – ranging from analog to digital computers – over the course of sixty years. His work was displayed in countless exhibitions, including the Venice Biennale in 1970. He was elected a member of the Vienna Künstlerhaus. In addition, as a co-founder of the ars electronica in Linz, Franke was crucial to the success story of this unique art, media, and technology forum.

In addition to producing graphics, Franke engaged frequently with the conception of moving sequences, especially exploring the connection of image-sound compositions. As early as 1982, he already developed programs on the Apple GS, which used a midi interface to control moving image sequences through music. He also realized such projects with other artists, for instance, Astropoeticon (1979) created in collaboration with the painter Andreas Nottebohm, the musician Walter Haupt, and his good friend Manfred P. Kage. Another important example is Hommage à E. M. for artware 1989, a “digital ballet” with music by Klaus Netzle, in which a dancer performs with her electronically alienated mirror image generated by her own movements. With these and other works, Franke extensively influenced the development of media art.

Herbert W. Franke contributed significantly to the scene with the exhibition entitled Wege zur Computerkunst (engl. On the Eve of Tomorrow), which in collaboration with the Goethe Institute, showed the first major overview of digital art of more than 200 countries in the 1970s. Only in recent years has “art by the machine” begun to interest traditional museums as a branch of contemporary art. Franke, who from the very start was firmly convinced of the future importance of this art movement, has assembled a unique collection of computer graphics, including works from respected international artists alongside his own, documenting 50 years of this development. The historical part of this collection has passed into the possession of the Kunsthalle Bremen, where it was presented in an extensive exhibition in 2007 for the first time.

Herbert W. Franke as a Publicist and Writer

As a physicist, Herbert W. Franke was predestined to bring science and technology closer to the general public through his talent for writing, which became apparent early on. About one third of his nearly fifty books as well as countless magazine articles, belong to popular nonfiction. In 1992, he received the Karl Theodor Vogel Prize for technology journalism. Franke rapidly established himself as a literary writer. Already in the 1950s, he published his first works, which appeared in the prestigious Austrian literary magazine Neue Wege, in which literary figures such as H. C. Artmann, Friederike Mayröcker, and Ernst Jandl were introduced to a broad readership in Austria for the first time.

Franke’s novels and stories do not deal with the predictions of future technologies nor with the forecast of our future mode of living, but rather with the intellectual examination of potential models of our future and their philosophical as well as ethical interpretations. In this respect, Franke attributes great importance to the seriousness of scientific and technological assessments of the future in terms of a feasibility analysis. In his opinion, a serious and reasonable analysis of future developments can in principle only be conducted on this foundation. Accordingly, Franke is not a typical representative of science fiction, but rather a visionary who as a novelist explores relevant questions concerning the societal future and human destiny at a high intellectual level.

Today Herbert W. Franke – an elected member of the PEN Club as well as the Graz Authors’ Assembly – is one of the most renowned authors of utopian literature in the German-speaking realm. For fifteen years, he was an author for the Suhrkamp publishing house, and after the reduction of the Phantastische Reihe, several novels were later published by the Deutschen Taschenbuch-Verlag dtv. In addition to 21 novels and more than 200 short stories, he wrote numerous audio plays, which were broadcast by many radio channels. Franke’s literary work has been awarded many prizes. In 2016, he was granted the title European Grand Master of Science Fiction by the European Science Fiction Society. Meanwhile, nearly all of his novels have been republished as e-books by Heyne, and a complete edition of his works consisting of 30 volumes is currently being released by the p.machinery publishing house – both in paperback and in a limited bibliophile hardcover edition.

Franke’s literary works have won many awards, among others he received the Kurd Lasswitz Prize, the greatest award in the sci-fi scene of Germany, and in 2016, he was awarded the title of European Grand Master of Science Fiction by the European Science Fiction Society.

Herbert W. Franke as a Scientist

Although Franke always worked as a freelancer after obtaining his doctorate, he made valuable contributions to foundational research. As a “private scholar”, the likes of which are rarely found in our scientific community today, he worked theoretically for many years in several specialized fields and published remarkable papers. . His ideas based on cybernetics have only recently been confirmed by the latest findings in neurobiology. Furthermore, Franke also taught his far-sighted theoretical ideas, and shared his experience as a pioneer of algorithmic art at the University of Munich and at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich for two decades.

As early as the mid-fifties, he recognized that the mathematically defined concept of continuity, like symmetry, shares a similar significance in the perception of art. As a theoretical physicist fascinated by the principle of interaction in systems, he also engaged early on with inquiries of cybernetics. In this respect, he was particularly interested in questions concerning the correlations between perceptual processes and art. Franke’s Rationales Kunstmodell, a contribution to the textbook Kybernetische Ästhetik published in the 1960s, understood perception as the basis of aesthetics and thus, art as a construct intelligible with the aid of information theory. He visualized the pattern of effects in a flow chart and traced the aesthetic function of emotions back to a rational, evolutionary basis. By means of his multilevel model, he was able to explain the long-term effects of art. In addition, he proposed a hypothesis on creativity based on random processes in the brain, which also suggested a model of the dream. Here again, Franke, a pioneer of information aesthetics, was a step ahead of his time. His ideas based on cybernetics have only recently been confirmed by the latest findings in neurobiology. Furthermore, Franke also taught his far-sighted theoretical ideas, and shared his experience as a pioneer of algorithmic art at the University of Munich and at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich for two decades.

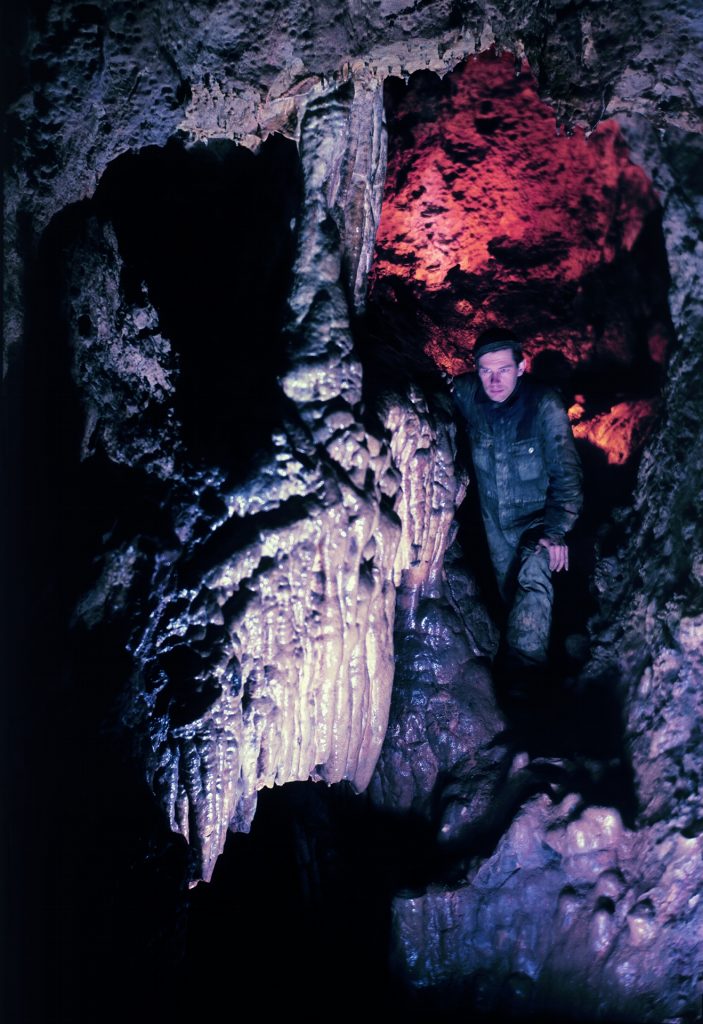

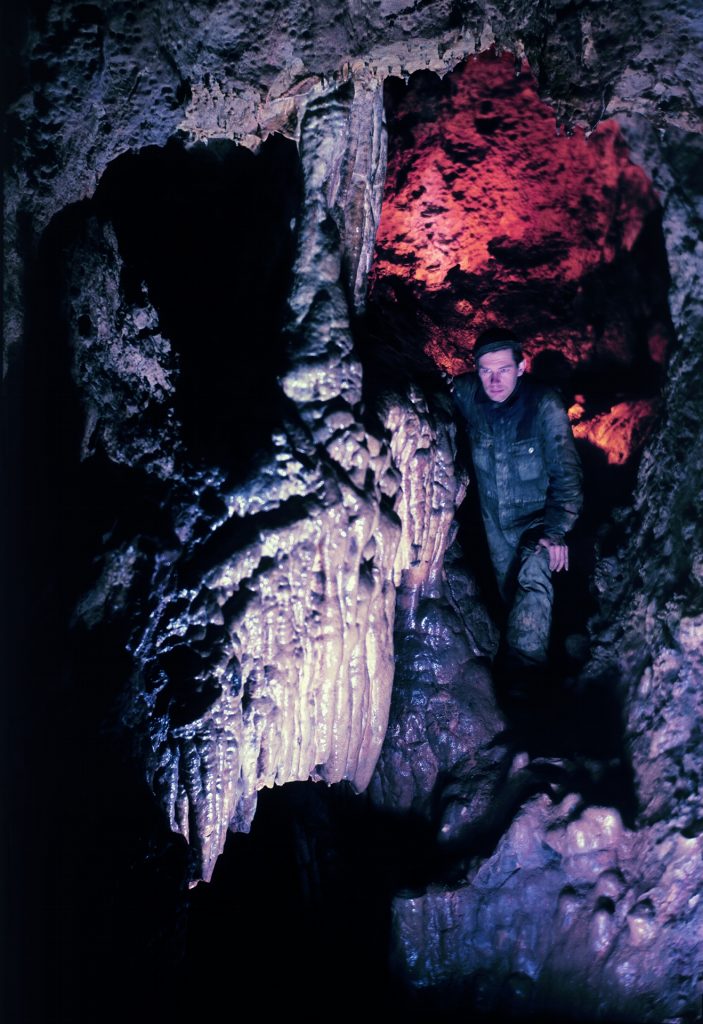

Photo documents of Franke’s historic cave explorations from 1952 to 1980

Since his student days, he had been involved as a speleologist in questions concerning the history of the formation of karst caves. During numerous expeditions to alpine caves, he made observations, which he then incorporated into his theoretical work. As early as 1951 – only two years after the discovery of Libby’s natural radiocarbon as a means of determining the age of organic substances – Franke concluded astonishingly that this method could also be useable in the special case of dating non-organic substances, i.e., cave sinter.

However, his paper published in the renowned Naturwissenschaften in 1951 was initially met with great skepticism and rejection. It took years until physicists of the University of Heidelberg took an interest in an experimental verification of his theoretical considerations. In collaboration with Franke, they proved the practical feasibility and thus, established the now common method of determining the age of dripstones using the C14-method.

ice cave at Dachstein, Austria

dripstone cave, isle of Sardinia, Italy

In the following years, together with Prof. Dr. Mebus A. Geyh of the then Lower Saxony State Office for Soil Research in Hannover, he systematically applied this method to cave sediments, which for the first time, resulted in exact data on the age of dripstones and physical measurement data for the temporal classification of terminal and post-glacial climatic periods. Today, the method for dating cave sinter has also become entrenched in the studies of geochronology, and is a key building block for climate research of the ending ice age. Consequently, Franke is one of the initiators of isotope based Palaeoclimatological research. Moreover, long before the first NASA images were taken, he deduced theoretically that enormous cave systems exist on Mars.

Finally, he gave theoretical reasons for seeking a program instead of a world formula in order to describe not only the laws of nature, but also its initial conditions. On the basis of cellular automata, he dealt with fundamental considerations of such properties. In 1995, these findings were published in a philosophical-theoretical book entitled Das P-Prinzip.

In 2008, Franke was named Senior Fellow by the renowned Zuse Institute Berlin ZIB. In math goes art, a research project initiated by this institute, he investigated interactions between mathematics and art, especially in the context of three-dimensional worlds in the web. Since 2017, the ZKM Center for Art and Media in Karlsruhe has been building the Herbert W. Franke Archive.